-

Turkeys On The Spit 2:590:00/2:59

-

16 Tons 3:500:00/3:50

-

0:00/3:20

-

Tears 2:560:00/2:56

-

0:00/4:49

-

0:00/3:37

-

Nice Room For Girl 3:360:00/3:36

-

Little Ukulele 4:520:00/4:52

-

0:00/5:05

-

Monkey Puzzle 2:160:00/2:16

-

0:00/4:09

-

Click On The Icon 4:440:00/4:44

-

0:00/4:00

-

0:00/4:01

-

0:00/6:07

-

0:00/4:01

-

0:00/4:38

-

0:00/3:58

-

0:00/3:40

-

0:00/2:34

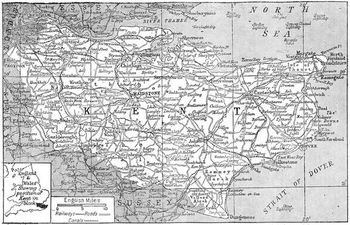

Men of Kent or Kentish Men?

A Man/Maid of Kent is a male/female who was born east of the River Medway

and a Kentish Man/Maid is one who was born west of the Medway.

The Kingdom of Kent

By the early 6th century AD, Kent was one of a number of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which had emerged in the south-east of England following the initial wave of settlement by Germanic peoples. Closely linked to mainland Europe, Kent was the richest and most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms during the late 6th and early 7th centuries.

Kent was also one of the first Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to be converted to Christianity. It already had contacts with the Christian Frankish culture of Gaul. King Ethelbert was married to a Frankish princess when the Roman monk Augustine arrived in 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons. Ethelbert was baptised and Augustine founded a monastery at Canterbury and was enthroned as its first archbishop in 601. Canterbury remains the premier archbishopric in England to this day.

Kent was a prosperous region. Kentish gold coins were already being issued before 600 – the first Anglo-Saxon coins. Later ones bear the name of the king, Eadbald (reigned 616-40). They were probably minted in East Anglia and Wessex as well as Kent. Gold supplies eventually dwindled and were replaced by silver by the end of the 7th century. By then, Kent, Surrey and Sussex had been annexed by the kingdom of Wessex. The Kentish dynasty became sub-kings and finally disappeared in 798.

This tremissis (shilling) is the first coin bearing the name of an English king – Eadbald of Kent. The earliest Anglo-Saxon coins, copying those of the Romans or other Germanic tribes, were issued about 600. Eadbald became a Christian in the middle of his reign and the coin bears the symbol of the cross.

& Kentish Kings

Hengest c.455-488

Aesc alias Oeric Oisc 488-512

Octa 512-540

Eormenric 540-560

Aethelbert I 560-616

Eadbald 616-640

Earconbert 640-664

Ecgbert I 664-673

Hlothere 673-685

Eadric 685-686

Mul 686-687

Interregnum 687-688

Oswine 688-690

Wihtraed 690-725

Aethelbert II 725-762

Eanmund 762-764

Heabert 764-765

Ecgbert II 765-772

Under Direct Mercian Rule 772-776

Sub-Kings under Mercian Rule

Ecgbert II 776-785 (again)

Ealhmund 784-785 (joint)

Ecgbert II (again) 784-785

Under Direct Mercian Rule 785-796

Kentish Rule

Eadbert Praen 796-798

Mercian Sub-King

Cuthred 798-807

Under Direct Mercian Rule 807-823

Mercian Sub-King

Baldred 823-824

Wessex Sub-Kings

Aethelwulf 824-839

Aethelstan 839-851

Aethelbert 851-860

Kent merged with the Kingdom of Wessex in 860

The History of Kent ©KKC

Kent was settled well before most other parts of England and has the oldest recorded place name in the British Isles. The County's history is closely bound up in its proximity to mainland Europe. Archeological remains from prehistoric times show clear links between Kent and Northern Europe, as well as a land link.

When Julius Caesar briefly invaded Kent in 55 and 54 BC he found it the most civilised part of Britain, colonised by the Belgae from Northern France. When the Romans again invaded in 43AD, this time to settle permanently, they colonised Kent along the Portus Lamanus from Richborough, rapidly establishing important centres throughout the County, and the remains of one at Lullingstone include an early Christian chapel.

The Roman legions abandoned Britain in the early fifth century to defend their empire nearer home. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Vortigern, the British ruler in Kent invited the mercenaries Hengist and Horsa to defend his principality from outside attack. They are said to have landed at Ebbsfleet near Ramsgate in 448 or 449 AD. By the end of the fifth century the Saxon kingdom of Kent had been firmly established. Under its king, Ethelbert, (560-616), Kent became one of the most advanced Saxon kingdoms in England

It was to Kent that Pope Gregory sent his missionaries under Augustine to begin their preaching of the gospel of Christianity to the English people. Augustine and his 40 companions landed at Ebbsfleet in 597. They were well received and instead of moving on to London as they had planned, they established their first cathedral at Canterbury. Seven years later another was built at Rochester. Augustine was the first archbishop, and since then the Archbishop of Canterbury has been the senior bishop of all England.

After the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, the new king, William I made his half brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, Earl of Kent. But Odo proved corrupt and the Normans and the men of Kent turned against him. After the release of Odo from prison in 1087 the Kentish levies helped the Normans to defeat him at the battle of Rochester. They were the seed of the first English army.

Within a century the capital of the English kings had moved from Winchester to London, and Kent's proximity to the new capital, together with its prime trading position, increased its political importance. Castles were built to defend the County. The most important were at Dover, Rochester and Canterbury. Henry VIII later built the castles in the Downs at Sandgate, Walmer and Deal to protect the Kent coast. But the closeness of London also made Kent a hot bed of political radicalism. The County played an important part in the peasants' revolt of 1381, and in various subsequent rebellions right up to the English Civil Wars of the1640s when there was fighting in the streets of Maidstone, and the 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688/9 when James II fled into exile from Faversham.

Many people left Kent in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to begin new lives in America; and were joined by hundreds of Kent poor who emigrated to the United States of America in the nineteenth century.

Unlike many parts of England, Kent had no single, powerfull and owning family. Before the reformation much of the land was owned by the two cathedrals and nearly 80 other monasteries and religious houses established in Kent. Cities and towns also held land. Non-ecclesiastical holdings were made smaller by the Kentish custom of gavel kind, or partible inheritance, whereby estates did not evolve to the eldest surviving son but were divided equally between all the male children after their father's death.

However, by the sixteenth century a number of significant landed families began to emerge such as the Knatchbulls of Mersham-le-Hatch, the Sackvilles of Knole and the Sidneys of Penshurst. With them came enclosure, most of which was completed in Kent by the end of the seventeenth century.

As with families, so with towns. Kent had no single natural urban centre but several towns of medium size. As local administration developed Kent was divided into two units, East (Men of Kent), administered from Canterbury, and West (Kentish Men), from Maidstone. In 1814 these two separate administrations were merged and Maidstone became the county town.

Kent's position as the nearest point of England to the continent of Europe has always made it vulnerable to invasion. The Hythe military canal was built for use to deter Napoleon in 1792 and garrisons were increased in many Kent towns. Bicycle units were set up in the 1st and 2nd World Wars to carry messages from special Control centres built underground. Many soldiers returning from Dunkerque landed on the Kent coast. The so-called Baedecker reprisal raids and other German bombing raids changed Canterbury and Dover forever; and Kent was the chief victim of the V1 and V2 rocket attacks launched from Germany and Calais in1943 and 1944 against Biggin Hill airport and parts of London.

The building works and extensive road system connected with the Channel Tunnel has changed the face of East Kent. We share many links with our neighbours across the Channel and the tunnel has brought us closer and has begun to affect the lives of the people of Kent as never before. Kent is the main Gateway between the UK and mainland Europe, with the International Station, Ashford is close in time to Lille as to London. The opening of the Channel Tunnel has had the greatest impact on the County's communication links and economic structure since the first trading forays of the Belgae from Northern France around 400BC.

Ease of access by water to London developed Chatham and Sheerness as dockyard towns, and Margate and Ramsgate as seaside resorts. All the towns along the eastern coast were significant either as commercial ports or in the defence of the realm.

Dover, Hythe, New Romney and Sandwich were four of the original five 'Cinque Ports'. Inland on the borders with Sussex important cloth and iron industries developed from the fifteenth century. Many paper mills were setup in the seventeenth century where sufficient water was available. Tunbridge Wells became a fashionable spa town in the1670s. Elsewhere in the County the dominant occupation was horticulture and the growing of hops for brewing. The hop, iron and cloth industries have provided the Kent landscape with two of its most prominent landmarks, the oast houses used for drying hops and the wealden hall houses of the Kent iron masters and cloth manufacturers.

Recent Developments

From the 1750s those parts of Kent nearest to London began to develop as suburbs of the capital. The County boundary was adjusted in 1889 when the present boroughs of Greenwich and Lewisham became part of London. To these were added, in 1965, the present boroughs of Bromley and Bexley.Further parts of Kent lying between the A21 and the M25 became, in 1974, London Boroughs but remain part of historic Kent.

Much of West Kent is now London commuter territory and towns like Maidstone, Sevenoaks and Tonbridge have expanded rapidly in size and population. The coming of the railways in the mid-nineteenth century was responsible for reviving the fortunes of Folkestone and for transforming Ashford from a sleepy market town to the centre of railway communications in Kent.

During the war both Canterbury and Dover were heavily bombed by Germany and received numerous V1 and V2 rocket attacks from Calais during 1943. The subsequent rebuilding of Canterbury and the enlargement of towns like Maidstone and Dover since 1963 has changed much of Kent. The building works and extensive road system connected with the Channel Tunnel has had the greatest impact on the County's communication links and economic structure since the first trading forays of the Belgae from northern France around about 400 BC.

Horsa, according to tradition, was the brother of Hengest. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 455 says that "Her Hengest ⁊ Horsa fuhton wiþ Wyrtgeorne þam cyninge, in þære stowe þe is gecueden Agælesþrep, ⁊ his broþur Horsan man ofslog; ⁊ æfter þam Hengest feng to rice ⁊ Æsc his sunu." ("Here Hengest and Horsa fought against King Vortigern in the place that is called Aylesford, and his brother Horsa was killed, and after that Hengest and his son Æsc took the kingdom."

Romano-British Ceint (Wiki)

The origins of Kent are obscure but the boundaries of the realm are likely to correspond to the ancient tribal lands of the Brythonic Cantiaci tribe or Ceint after which the kingdom is named. Caesar referred to Cingetorix, Carvilius, Taximagulus and Segovax as kings of the four regions of Cantiacia. Later kings are known from their coins, including Dubnovellaunus, Vosenos, Eppillus, and Amminus.

The Kentish coastline was known as the Saxon Shore and was guarded by a series of very effective fortresses. After the evacuation of the last Roman legions from Britain a number of Jutish ships made landfall on the shores of Britain. The British ruling council was offering them payment in return for federati service defending the realm in the north from the incursions of Picts and Scots. According to legend they were promised provisions and offered the island of Ynys Ruym - now known as Thanet - in perpetuity to use as a base for their operations. It is recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles that their leader, Hengist, advised;

Take my advice and you will never fear conquest from any man or any people, for my people are strong. I will invite my son and his cousin to fight against the Irish [the Scoti], for they are fine warriors.

Apparently the Jutes assaulted the enemy and brought much needed relief to the beleaguered Romano-British communities of the north. It is further said that the British king Vortigern married Rowena, the daughter of Hengist with the Cantiaci civitas (Kent) as the bride-gift.

Gwrangon was king of Ceint in the time of Vortigern according to Nennius. The word 'king' may be misleading and it is more likely that the 'province' of the Cantiaci was ruled jointly by a civil governor (Gwrangon?) and a military governor, according to classic Roman institutions and that Hengest became the new military governor.

The establishment of barbarian bases inland rendered the extensive coastal forts of the Saxon Shore almost useless as the 6th Century British monk Gildas Sapiens laments;

They sealed its [Britain's] doom by inviting in among them (like wolves in to the sheep fold), the fierce and impious Saxons [sic] a race hurtful both to God and men, to repel the invasions of the northern nations. Nothing was ever so pernicious to our country, nothing was ever so unlucky. What palpable darkness must have enveloped their minds-darkened desperate and cruel! Those very people whom, when absent, they dreaded more than death itself, were invited to reside, as one may say, under the selfsame roof.

The Jutes began making ever increasing demands for provisions from their hosts who became increasingly divided and fractious. Each time the Britons threatened to withhold the supplies the Jutes threatened to break the alliance and ravage the country. Vortimer - Vortigern's own son - assembled an army and attacked the Jutes. Vortimer died at the Battle of Aylesthrep alongside the Jutish co-ruler of Kent - Horsa. The next year the Jutes were attacked again at the Battle of Creganford.

Reputedly, a banquet took place ostensibly to seal a peace treaty between the Britons and their Germanic foes which may have involved the cession of modern-day Essex. As told, the story claims that the "Saxons"—which probably includes Angles and Jutes—arrived at the banquet armed, surprising the British, who were slaughtered. This event was dubbed the Night of the Long Knives by Geoffrey of Monmouth and is the original event to bear that name. The only escapees from this slaughter were said to be Vortigern himself, and Saint Abban the Hermit. The historical existence of this event or persons involved in it is conjectural as textual evidence is weak and begins in the 7th century.

The British government under Vortigern unravelled and civil war was spreading across the country. Further actions took place at the Battle of Wippedsfleot but Kent was never recovered. The pacified territory of Ceint was from now on known as Cantware and its kings traced their lineage from Hengist.

Jutish Cantware

The first securely datable event in the kingdom is the arrival of Augustine with 40 monks in 597. Because Kent was the first kingdom in England to be established by the Germanic invaders it was able to become relatively powerful in the early Anglo-Saxon period.

Kent seems to have had its greatest power under Æthelbert at the beginning of the 7th century: Æthelbert was recognized as Bretwalda until his death in 616, and was the first Anglo-Saxon king to accept Christianity, as well as the first to introduce a written code of laws in 616. After his reign, however, the power of Kent began to decline: by the middle of the century, it seems to have been dominated by more powerful Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

In 686, Kent was conquered by Caedwalla of Wessex; within a year, Caedwalla's brother Mul was killed in a Kentish revolt, and Caedwalla returned to devastate the kingdom again. After this, Kent fell into a state of disorder. The Mercians backed a client king named Oswine, but he seems to have reigned for only about two years, after which Wihtred became king. Wihtred did a great deal to restore the kingdom after the devastation and tumult of the preceding years, and in 694 he made peace with the West Saxons by paying compensation for the killing of Mul.

The history of Kent following the death of Wihtred in 725 is one of fragmentation and increasing obscurity. For the 40 years that followed, two or even three kings typically ruled simultaneously. It may have been this sort of division that made Kent the first target of the rising power of Offa of Mercia: in 764, he gained supremacy over Kent and began to rule it through client kings. By the early 770s, it appears Offa was attempting to rule Kent directly, and a rebellion followed. A battle was fought at Otford in 776, and although the outcome was not recorded, the circumstances of the years that followed suggest that the rebels of Kent prevailed: Egbert II and later Ealhmund seem to have ruled independently of Offa for nearly a decade thereafter. This did not last, however, as Offa firmly re-established his authority over Kent in 785.

From 785 until 796, Kent was ruled directly by Mercia. In the latter year, however, Offa died, and in this moment of Mercian weakness a Kentish rebellion under Eadbert Praen temporarily succeeded. Offa's eventual successor, Coenwulf, reconquered Kent in 798, however, and installed his brother Cuthred as king. After Cuthred's death in 807, Coenwulf ruled Kent directly. Mercian authority was replaced by that of Wessex in 825, following the latter's victory at the Battle of Ellandun, and the Mercian client king Baldred was expelled.

In 892, when all southern England was united under Alfred the Great, Kent was on the brink of disaster. A hundred years earlier pagan Vikings had begun their raids on these shores—they first attacked Lindisfarne on the coast of Northumbria killing the monks and devastating the Abbey. They then made successive raids further south until in the year 878 the formidable Alfred defeated them, later drawing up a treaty allowing them to settle in East Anglia and the North East. However, countrymen from their Danish homeland were still on the move and by the late 880s Haesten, a highly experienced warrior-leader, had mustered huge forces in northern France having besieged Paris and taken Brittany.

Up to 350 Viking ships sailed from Boulogne to the south coast of Kent in 892. A massive army of between five and ten thousand men with their women, children and horses came up the now long-lost Limen estuary (the east-west route of the Royal Military Canal in reclaimed Romney Marsh) and attacked a Saxon fort near lonely St Rumwold's church, Bonnington, killing all inside. They then moved on and over the next year built their own giant fortress at Appledore. On hearing of this, resident Danes in East Anglia and elsewhere broke their promises to Alfred and rose up to join in. At first they made lightning raids out of Appledore (one razing a large settlement, Seleberhtes Cert, to the ground - now present day Great Chart near Ashford) later the whole army moved further inland and engaged in numerous battles with the English, but after four years they gave up. Some retreated to East Anglia and others went back to northern France. There they were the forebears of the Normans who returned in triumph less than two centuries later.

Most of lands of the kingdom are within the bounds of the traditional County of Kent.

Wat Tyler And The Men Of Kent

Author: Charles Morris

In that year of woe and dread, 1348, the Black Death fell upon England. Never before had so frightful a calamity been known; never since has it been equalled. Men died by millions. All Europe had been swept by the plague, as by a besom of destruction, and now England became its prey. The population of the island at that period was not great,--some three or four millions in all. When the plague had passed more than half of these were in their graves, and in many places there were hardly enough living to bury the dead.

We call it a calamity. It is not so sure that it was. Life in England at that day, for the masses of the people, was not so precious a boon that death had need to be sorely deplored. A handful of lords and a host of labourers, the latter just above the state of slavery, constituted the population. Many of the serfs had been set free, but the new liberty of the people was not a state of unadulterated happiness. War had drained the land. The luxury of the nobles added to the drain. The patricians caroused. The plebeians suffered. The Black Death came. After it had passed, labour, for the first time in English history, was master of the situation.

Labourers had grown scarce. Many men refused to work. The first general strike for higher wages began. In the country, fields were left untilled and harvests rotted on the ground. "The sheep and cattle strayed through the fields and corn, and there were none left who could drive them." In the towns, craftsmen refused to work at the old rate of wages. Higher wages were paid, but the scarcity of food made higher prices, and men were little better off. Many labourers, indeed, declined to work at all, becoming tramps,--what were known as "sturdy beggars,"--or haunting the forests as bandits.

The king and parliament sought to put an end to this state of affairs by law. An ordinance was passed whose effect would have made slaves of the people. Every man under sixty, not a land-owner or already at work (says this famous act), must work for the employer who demands his labour, and for the rate of wages that prevailed two years before the plague. The man who refused should be thrown into prison. This law failed to work, and sterner measures were passed. The labourer was once more made a serf, bound to the soil, his wage-rate fixed by parliament. Law after law followed, branding with a hot iron on the forehead being finally ordered as a restraint to runaway labourers. It was the first great effort made by the class in power to put down an industrial revolt.

The peasantry and the mechanics of the towns resisted. The poor found their mouth-piece in John Ball, "a mad priest of Kent," as Froissart calls him. Mad his words must have seemed to the nobles of the land. "Good people," he declared, "things will never go well in England so long as goods be not in common, and so long as there be villains and gentlemen. By what right are they whom we call lords greater folk than we? On what grounds have they deserved it? Why do they hold us in serfdom? If we all came of the same father and mother, of Adam and Eve, how can they say or prove that they are better than we, if it be not that they make us gain for them by our toil what they spend in their pride? They are clothed in velvet, and warm in their furs and their ermines, while we are covered with rags. They have wine and spices and fair bread; and we have oat-cake and straw, and water to drink. They have leisure and fine houses; we have pain and labour, the rain and the wind in the fields. And yet it is of us and of our toil that these men hold their state."

So spoke this early socialist. So spoke his hearers in the popular rhyme of the day:

"When Adam delved and Eve span,

Who was then the gentleman?"

So things went on for years, growing worse year by year, the fire of discontent smouldering, ready at a moment to burst into flame.

At length the occasion came. Edward the Third died, but he left an ugly heritage of debt behind him. His useless wars in France had beggared the crown. New money must be raised. Parliament laid a poll-tax on every person in the realm, the poorest to pay as much as the wealthiest.

Here was an application of the doctrine of equality of which the people did not approve. The land was quickly on fire from sea to sea. Crowds of peasants gathered and drove the tax-gatherers with clubs from their homes. Rude rhymes passed from lip to lip, full of the spirit of revolt. All over southern England spread the sentiment of rebellion.

The incident which set flame to the fuel was this. At Dartford, in Kent, lived one Wat Tyler, a hardy soldier who had served in the French wars. To his house, in his absence, came a tax-collector, and demanded the tax on his daughter. The mother declared that she was not taxable, being under fourteen years of age. The collector thereupon seized the child in an insulting manner, so frightening her that her screams reached the ears of her father, who was at work not far off. Wat flew to the spot, struck one blow, and the villainous collector lay dead at his feet.

Within an hour the people of the town were in arms. As the story spread through the country, the people elsewhere rose and put themselves under the leadership of Wat Tyler. In Essex was another party in arms, under a priest called Jack Straw. Canterbury rose in rebellion, plundered the palace of the archbishop, and released John Ball from the prison to which this "mad" socialist had been consigned. The revolt spread like wildfire. County after county rose in insurrection. But the heart of the rebellion lay in Kent, and from that county marched a hundred thousand men, with Wat Tyler at their head, London their goal.

To Blackheath they came, the multitude swelling as it marched. Every lawyer they met was killed. The houses of the stewards were burned, and the records of the manor courts flung into the flames. A wild desire for liberty and equality animated the mob, yet they did no further harm. All travellers were stopped and made to swear that they would be true to King Richard and the people. The king's mother fell into their hands, but all the harm done her was the being made to kiss a few rough-bearded men who vowed loyalty to her son.

The young king--then a boy of sixteen--addressed them from a boat in the river. But his council would not let him land, and the peasants, furious at his distrust, rushed upon London, uttering cries of "Treason!" The drawbridge of London Bridge had been raised, but the insurgents had friends in the city who lowered it, and quickly the capital was swarming with Wat Tyler's infuriated men.

Soon the prisons were broken open, and their inmates had joined the insurgent ranks. The palace of the Duke of Lancaster, the Savoy, the most beautiful in England, was quickly in flames. That nobleman, detested by the people, had fled in all haste to Scotland. The Temple, the head-quarters of the lawyers, was set on fire, and its books and documents reduced to ashes. The houses of the foreign merchants were burned. There was "method in the madness" of the insurgents. They sought no indiscriminate ruin. The lawyers and the foreigners were their special detestation. Robbery was not permitted. One thief was seen with a silver vessel which he had stolen from the Savoy. He and his plunder were flung together into the flames. They were, as they boasted, "seekers of truth and justice, not thieves or robbers."

Thus passed the first day of the peasant occupation of London, the people of the town in terror, the insurgents in subjection to their leaders, and still more so to their own ideas. Many of them were drunk, but no outrages were committed. The influence of one terrible example repressed all theft. Never had so orderly a mob held possession of so great a city.

On the second day, Wat Tyler and a band of his followers forced their way into the Tower. The knights of the garrison were panic-stricken, but no harm was done them. The peasants, in rough good humor, took them by the beards, and declared that they were now equals, and that in the time to come they would be good friends and comrades.

But this rude jollity ceased when Archbishop Sudbury, who had been active in preventing the king from landing from the Thames, and the ministers who were concerned in the levy of the poll-tax, fell into their hands. Short shrift was given these detested officials. They were dragged to Tower Hill, and their heads struck off.

"King Richard and the people!" was the rallying cry of the insurgents. It went ill with those who hesitated to subscribe to this sentiment. So evidently were the peasants friendly to the king that the youthful monarch fearlessly sought them at Mile End, and held a conference with sixty thousand of them who lay there encamped.

"I am your king and lord, good people," he boldly addressed them; "what will ye?"

"We will that you set us free forever," was the answer of the insurgents, "us and our lands; and that we be never named nor held for serfs."

"I grant it," said the king.

His words were received with shouts of joy. The conference then continued, the leaders of the peasants proposing four conditions, to all of which the king assented. These were, first, that neither they nor their descendants should ever be enslaved; second, that the rent of land should be paid in money at a fixed price, not in service; third, that they should be at liberty to buy and sell in market and elsewhere, like other free men; fourth, that they should be pardoned for past offences.

"I grant them all," said Richard. "Charters of freedom and pardon shall be at once issued. Go home and dwell in peace, and no harm shall come to you."

More than thirty clerks spent the rest of that day writing at all speed the pledges of amnesty promised by the king. These satisfied the bulk of the insurgents, who quietly left for their homes, placing all confidence in the smooth promises of the youthful monarch.

Some interesting scenes followed their return. The gates of the Abbey of St. Albans were forced open, and a throng of townsmen crowded in, led by one William Grindcobbe, who compelled the abbot to deliver up the charters which held the town in serfdom to the abbey. Then they burst into the cloister, sought the millstones which the courts had declared should alone grind corn at St. Albans, and broke them into small pieces. These were distributed among the peasants as visible emblems of their new-gained freedom.

Meanwhile, Wat Tyler had remained in London, with thirty thousand men at his back, to see that the kingly pledge was fulfilled. He had not been at Mile End during the conference with the king, and was not satisfied with the demands of the peasants. He asked, in addition, that the forest laws should be abolished, and the woods made free.

The next day came. Chance brought about a meeting between Wat and the king, and hot blood made it a tragedy. King Richard was riding with a train of some sixty gentlemen, among them William Walworth, the mayor of London, when, by ill hap, they came into contact with Wat and his followers.

"There is the king," said Wat. "I will go speak with him, and tell him what we want."

The bold leader of the peasants rode forward and confronted the monarch, who drew rein and waited to hear what he had to say.

"King Richard," said Wat, "dost thou see all my men there?"

"Aye," said the king. "Why?"

"Because," said Wat, "they are all at my command, and have sworn to do whatever I bid them."

What followed is not very clear. Some say that Wat laid his hand on the king's bridle, others that he fingered his dagger threateningly. Whatever the provocation, Walworth, the mayor, at that instant pressed forward, sword in hand, and stabbed the unprotected man in the throat before he could make a movement of defence. As he turned to rejoin his men he was struck a death-blow by one of the king's followers.

This rash action was one full of danger. Only the ready wit and courage of the king saved the lives of his followers,--perhaps of himself.

"Kill! kill!" cried the furious peasants, "they have killed our captain."

Bows were bent, swords drawn, an ominous movement begun. The moment was a critical one. The young king proved himself equal to the occasion. Spurring his horse, he rode boldly to the front of the mob.

"What need ye, my masters?" he cried. "That man is a traitor. I am your captain and your king. Follow me!"

His words touched their hearts. With loud shouts of loyalty they followed him to the Tower, where he was met by his mother with tears of joy.

"Rejoice and praise God," the young king said to her; "for I have recovered to-day my heritage which was lost, and the realm of England."

It was true; the revolt was at an end. The frightened nobles had regained their courage, and six thousand knights were soon at the service of the king, pressing him to let them end the rebellion with sword and spear.

He refused. His word had been passed, and he would live to it--at least, until the danger was passed. The peasants still in London received their charters of freedom and dispersed to their homes. The city was freed of the low-born multitude who had held it in mortal terror.

Yet all was not over. Many of the peasants were still in arms. Those of St. Albans were emulated by those of St. Edmondsbury, where fifty thousand men broke their way into the abbey precincts, and forced the monks to grant a charter of freedom to the town. In Norwich a dyer, Littester by name, calling himself the King of the Commons, forced the nobles captured by his followers to act as his meat-tasters, and serve him on their knees during his repasts. His reign did not last long. The Bishop of Norwich, with a following of knights and men-at-arms, fell on his camp and made short work of his majesty.

The king, soon forgetting his pledges, led an army of forty thousand men through Kent and Essex, and ruthlessly executed the peasant leaders. Some fifteen hundred of them were put to death. The peasants resisted stubbornly, but they were put down. The jurors refused to bring the prisoners in guilty, until they were threatened with execution themselves. The king and council, in the end, seemed willing to compromise with the peasantry, but the land-owners refused compliance. Their serfs were their property, they said, and could not be taken from them by king or parliament without their consent. "And this consent," they declared, "we have never given and never will give, were we all to die in one day."

Yet the revolt of the peasantry was not without its useful effect. From that time serfdom died rapidly. Wages continued to rise. A century after the Black Death, a labourer's work in England "commanded twice the amount of the necessaries of life which could have been obtained for the wages paid under Edward the Third." In a century and a half serfdom had almost vanished.

Thus ended the greatest peasant outbreak that England ever knew. The outbreak of Jack Cade, which took place seventy years afterwards, was for political rather than industrial reform. During those seventy years the condition of the working-classes had greatly improved, and the occasion for industrial revolt correspondingly decreased.